The Perimeter Path Biographies

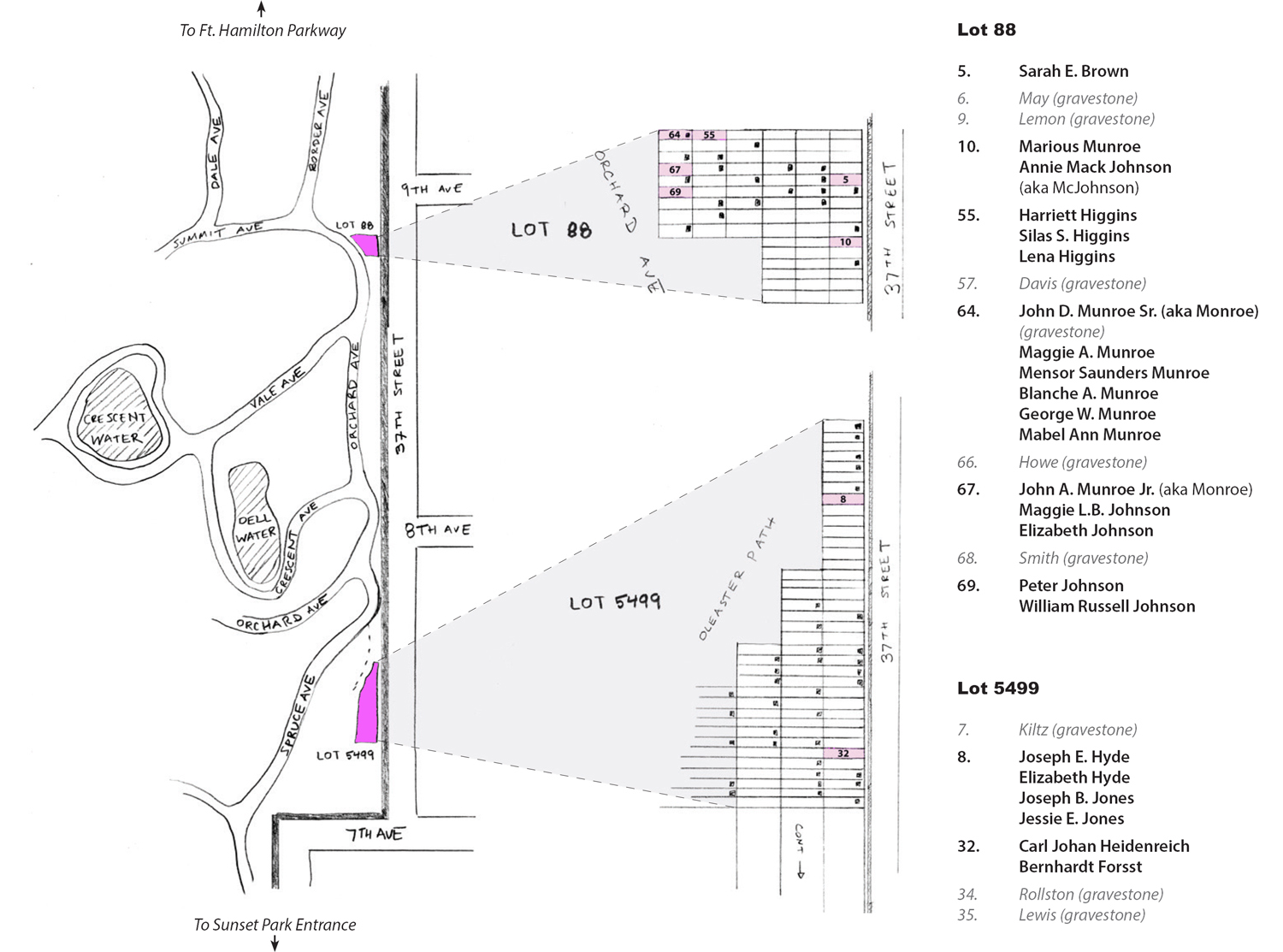

From selected unmarked graves in Lot 88 and Lot 5499 at The Green-Wood Cemetery

Lot 88

Click the names below to view biographies.

Grave 5: Sarah E. Brown

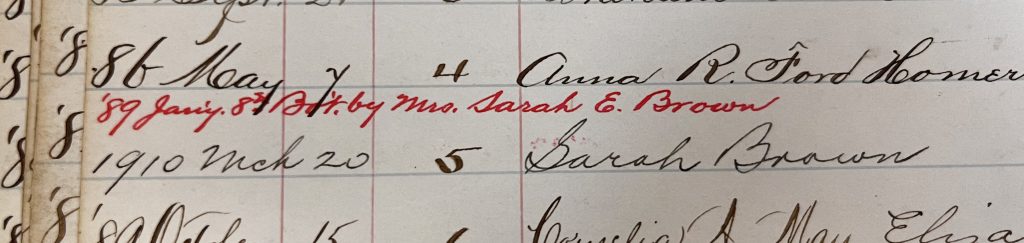

Sarah E. Brown, born abt 1841, died March 12, 1910, interred March 20, 1910.

Green-Wood’s burial ledger shows that Sarah E. Brown purchased her own burial plot on January 8, 1889, twenty-two years before she passed away on March 12, 1910. This is unusual for burials in public lots, which were typically purchased at the time they were needed, not in advance. Although we could not find further census records about Sarah, Green-Wood’s burial records describe her as a 69-year-old widow who was born in New York. She resided at 123 Evergreen Ave. in Queens, and died of acute parenchymatous nephritis, a kidney disease. She is buried alone.

I connected to this detail, one of the few pieces of information we have about Sarah, because of the agency and self-empowerment I read in her decision to make her own death plans. I believe that it was important for her to know, and be in control, of where she would be buried, and not leave this decision in the hands of others.

Grave 55: Harriett Higgins, Silas S. Higgins and Lena Higgins

Harriet Higgins, born abt 1827, died 4/18/1886, removed from Evergreens Cemetery and interred at Green-Wood 4/21/1887

Silas S. Higgins, born abt 1799, died 6/13/1876, removed from Evergreens Cemetery and interred at Green-Wood 4/21/1887

Lena Higgins, born abt 1859, died 2/10/1894, interred 2/12/1894

Harriet Higgins (1827-1886) and Silas S. Higgins (1799-1876) were the parents of Lena Higgins (1859-1894). Harriet and Silas were originally buried at Evergreens Cemetery in Queens. On April 21, 1887, both parents were disinterred from Evergreens and re-buried at Green-Wood in a plot Lena purchased. Lena lived nearby at 663 6th Avenue near 18th Street in Brooklyn; the new burial plot would bring her parents closer to her.

Silas S. Higgins (1799-1876) was born in New Jersey around 1799, and may have been born enslaved. Discrepancies in his birth date, which on several records is dated 1805, may have been intentional. New Jersey law provided that boys born to enslaved parents after 1804 would be indentured servants until age 25, eventually becoming free.

According to the 1855 NYS Census, Harriet Higgins (1827-1886) was born in District of Columbia around 1827, before slavery was made illegal (1850) and abolished (1862), which may indicate she was born enslaved. However, her death record states her place of birth as New Jersey. By 1850 records show she was married to Silas and living in New Jersey with children. It’s unclear whether the discrepancy in birthplace was a mistake, or an intentional change to protect her freedom.

Silas was around 15 years older than Harriet, and he was listed in the census as a laborer. Eight children were listed in Census records between 1850 and 1875 – Peter, Catherine, Lawrence, Rebecca, Elanor, William, Hendricks and Lena – although it is unknown whether some of the children died young, or were out of the house for later census records. In 1868, Silas was arrested and accused of cruelty to animals for allegedly turning out an old horse onto the commons without food or shelter. By 1870 Silas was no longer working, and his occupation was listed as a gardener, and Harriet as a housekeeper. Silas owned real estate, although by 1870 the property requirement for Black men to be eligible to vote in New York had been repealed and he would be eligible to vote regardless of property ownership. By the 1875 census, Silas was 80 years old and Lena was the only child still living at home. A year later, Silas passed away.

After Silas’ death it appears that his wife Harriet began to work outside the home. In 1886, the same year as her death, she was working as a laundress in Brooklyn. The cause of death was “Fanal erysipelas, delirium,” which may be a typo for “facial erysipelas.” Erysipelas is a painful bacterial skin rash that is often caused by Streptococci, and would be treatable today. Such an infection could have been caused by occupational exposure to contaminated water through broken or irritated skin.

Just six years later, at the age of 35, Lena Higgins (1859-1894) passed away and was buried with her parents. She never married and did not have children. Her occupation was listed as “servant.” Her cause of death was listed as “valvular disease of the heart, dropsey asthenia,” which may have indicated she suffered from a chronic illness. Dropsey refers to a retention of fluids that could have been caused by heart or kidney problems; asthenia refers to a loss of strength or general weakness. If she indeed had a chronic illness, that may have influenced her decision to move her parents final resting place closer to home.

Download Research Report for Harriet, Silas and Lena Higgins. Compiled by Lucy Redmond.

Overview: Munroe (aka Monroe) and Johnson Family Graves

The Munroes (aka Monroe) and Johnsons have multiple lots in Lot 88, in effect using the close proximity of the single graves as a family plot. Although it was common across the public lots to bury family members together in a single grave, which accommodates three adults, the Munroes and Johnsons purchased their plots at different times, with burials spanning from 1890 – 1918. It appears that the families were connected through at least one marriage. However, since we were unable to find the marriage records, the exact relations are unknown.

John D. Munroe (Sr.) (1846-1918) and his wife Maggie (Washington) Munroe (1862-1925) (both Grave 64) were active in the Bridge St. AME Church, where John was a trustee and Maggie was a deaconess, which may have been another point of connection for the families. Between 1854 and 1938, the Bridge St. AME Church (now located at 277 Stuyvesant Ave) was located at 309 Bridge St. This church was a center for Black activism in Brooklyn. Harriet Tubman once spoke there, and it was a known stop on the Underground Railroad. The church would have been within a two block radius from the two addresses where Munroes lived between 1900 – 1915: 94 Willoughby St. and 178 Duffield St.; as well as where William R. Johnson (1858-1914) (Grave 69) lived at 94 Johnson St. from 1896 until his death in 1914.

While the Munroes lived at both 94 Willoughby St. and 178 Duffield St., they took boarders, some of whom were born in the South: Virginia, District of Columbia, and Louisiana, who appeared to have been moving North as part of the Great Migration. One of the boarders, Arthur Quincy Martin, was the undertaker for multiple burials in Lot 88, including Marious Munroe (1861-1910) and Annie Mack Johnson (1871-1914) (both Grave 10), the brother and sister of John D. Munroe (Sr.)’s. There also appear to be other links between people interred in Lot 88 that suggest they may have known each other or shared community. This is a contrast to the burials in Lot 5499, which do not appear to share connections between separate plots.

Download Munroe (Monroe) and Johnson Family Overview. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Grave 10: Marious Munroe and Annie Mack Johnson

Marious Munroe (aka Monroe), born 1861, died December 9, 1910, interred December 12, 1910.

Annie Mack Johnson (aka Mc Johnson), born 1871, died April 28, 1914, interred May 1, 1914.

Marious Munroe (1861-1910) and Annie Mack Johnson (aka Mc Johnson) (1871-1914) are the brother and sister of John D. Munroe (Sr.)(1846-1918, Grave 64) and the aunt and uncle of John A. Munroe (Jr.) (1888-1918, Grave 67) and Mensor Saunders Munroe (1895-1916, Grave 64.)

Their parents were Hasty (aka Hastings) Monroe and Sarah (Alston) Monroe. Sarah and Hasty’s marriage record, dated July 30, 1866, from Carteret county North Carolina, listed their address as “slave.” The issue date was recorded as June 19, 1847, suggesting that the couple had been married for nearly twenty years, but because enslaved people did not have the right to marry, their marriage would not be legally recognized until after emancipation. This likely meant that Marious, who was born before emancipation, was born enslaved, while his sister Annie, born in 1871, was born free.

According to the 1870 census, 12-year-old Marious Munroe (Marius Monroe) was residing with his parents, Hasty and Sarah, and siblings Maria (14), John (10), Mary (8), Martha (4), and Susan (2), in Beaufort, North Carolina. In total, there are 8 identified siblings. Hasty, Maria, and Marious’ race was recorded as mulatto, whereas the rest of the family was recorded as Black. Mulatto was a racial category for mixed-race on the U.S. Census from 1850 to 1890 and in 1910 and 1920, and was generally based on outdated and offensive ideas about racial purity. At the time of the census, Marius, Maria, John, and Mary were attending school, and Hasty was working as a fisherman. Annie would be born the following year.

By the time of the New York State Census of 1892, Marious Munroe was residing in Long Island City, Queens. He was 32 years old and was working as a coachman. We know that two of his siblings, John D. and Annie also migrated to New York, but it’s unknown if other members of their family migrated north, or stayed in North Carolina.

By the 1900 census, 39-year-old Marious lives on East 88th Street with his wife Jane A. (46). They have been married for 5 years. They have a boarder, James Hastings Enos, a 3-year-old child. The census recorded that the child’s father was born in New York, and his mother was born in North Carolina, suggesting that James may be a relative of Marious.

Marious Munroe died on December 9, 1910, at the age of 49-years-old, in Manhattan. According to records from Green-Wood, his wife predeceased him, although they are not buried together. Marious’ cause of death was nephritis, a kidney disease.

Download Research Report for Marious Munroe. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

His sister, Annie Mack Johnson (aka Mc Johnson) (1871-1914) is buried with him. Annie was born in Beaufort, North Carolina in 1871. The first record for her in New York was the 1910 census, which shows that 39-year-old Annie resided on 122nd Street in Manhattan, with her daughter Eleyettia (17). Both are described as mulatto. Annie was widowed at this time and had given birth to four children, two of whom were still living. Mother and daughter were both working as servants in the home of George R. Vandewater, a white, English clergyman, and his wife Cornelia T.

Four years later, on April 28, 1914, Annie passes away at age 43 after a year-long illness. Her cause of death is listed as nephritis, a kidney disease, and intestinal obstruction. At the time of her death she was living with her brother, John D. Munroe (Sr.) (1846-1918, Grave 64) at 178 Duffield St, suggesting that she was no longer able to work. Her daughter, Eleyettia, was named the executor of her estate. Her obituary was published in the newspaper the New York Age.

Download Research Report for Annie Mack Johnson (aka Mc Johnson). Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Grave 64: John D. Munroe (Sr.), Maggie A. Munroe, Mensor Saunders Munroe, Mabel Ann Munroe, Blanche A Munroe, and George W. Munroe

John D. Munroe (Sr.) (aka Monroe), born 1846, died February 21, 1918, interred February 24, 1918.

Maggie A. Munroe, born 1862, died April 26, 1925, interred April 30, 1925.

Mensor Saunders Munroe, born 1895, died November 22, 1916, interred November 26, 1916.

Mabel Ann Munroe, age 1 year 8 months and 20 days, died May 14, 1886, interred May 16, 1886.

Blanche A. Munroe, age 9 months 8 days, died June 14, 1887, interred June 16, 1887.

George W. Munroe, age 6 months 8 days, died March 15, 1891, interred March 18, 1891.

John D. Munroe (Sr.)(1846-1918) is the only member of the Munroe and Johnson families with a grave marker. Green-Wood’s records show that there are six burials in Grave 64, although they are not memorialized. This includes his wife, Maggie A. Munroe (1862-1925), who outlived her husband, as well as four of their children, who predeceased them both. Mabel Ann (1884-1886), Blanche A. (1886-1887) and George W. (1890-1891) were all infants at the time of their death. Mensor Saunders Munroe (1895-1916) was 21 years old and passed away from pneumonia.

Census records show that Maggie gave birth to six children. Three of them passed away as infants. Two, Mensor and John (Jr.) (1888-1918, Grave 67) live to adulthood, but die young. Her son William was the only child to outlive his mother. Census record show that William lived in Manhattan through at least the 1950s, where he worked as a U.S. Postal clerk. His last recorded address was on St. Nicholas Ave in the Sugar Hill neighborhood of Harlem.

John D. Munroe (Sr.) was a civil war veteran and a trustee of the Bridge St. AME Church. His wife Maggie, was a deaconess. His extensive biography, detailing his service in the war and his community involvement, is available through Green-Wood’s Civil War Veteran’s project, located here.

John (Sr.) was reported to have died instantly when struck by a truck at Amity and Henry Streets in Brooklyn, on February 21, 1918, and died of cerebral fracture. He was 71 years old. Arthur Quincy Martin, a former boarder in his home, served as his undertaker. Maggie survived him by seven years. She passed away on April 26, 1925, at age 65. Her cause of death was carcinoma. Newspaper records from The New York Age record gifts of flowers and altar cloths in her memory during services at the Bridge St. AME church through 1930. The donors included Arthur Q. Martin, her son William, and others.

Grave 67: John A. Munroe (Jr.), Elizabeth Johnson and Maggie L.B. Johnson

John A. Munroe (Jr) (aka Monroe), born July 27, 1888, died October 2, 1918, interred October 5, 1918.

Elizabeth Johnson, born 1861, died May 25, 1890, interred May 28, 1890.

Maggie L.B. Johnson, born 1878, died September 19, 1903, interred September 23, 1903.

John A. Munroe (Jr.) (1888-1918) was the son of John D. Munroe (Sr.) and Maggie Munroe (both Grave 64). He is interred with Maggie L.B. Johnson (aka Maggie L. Brown Johnson) (1878-1903) and Elizabeth Johnston (1861-1890), although the relationship of the women to John (Jr.) and the Munroe family is not clear.

We could not find information about John (Jr.)’s early life, but by the 1900 census, John (Jr.)(11) was living with his parents and two younger brothers, William (7) and Mensor (5) at 94 Willoughby St. His father was working as a carpenter and his mother as a dressmaker. There were several boarders living with them: Alfred C. Cowen, Robert B Warmsley, Albert Smith, Annie Smith, Maggie Carpenter, and Ellen Williams. Several of the boarders were born in southern states, including Kentucky, Louisiana, District of Columbia and Virginia, and two were from the northern states of New York and Michigan.

In 1905, at age 16, the census records that John (Jr.) was attending school. In 1915, at age 27, he was working as a porter. His family had moved to 178 Duffield St. and continued to have boarders: Arthur Quincey Martin and his wife Harriet Martin, Harry Gibbs, John Dueva, and John Boyd. Arthur Quincy Martin appeared to have a close relationship to the Munroe family, later serving as the undertaker for several family burials and described in The New York Age as member of the Bridge St. AME Church. Another boarder, John Boyd, is listed as a church sexton.

On September 12, 1918, 30-year-old John (Jr.) registers for the World War I draft. At this time his occupation was listed as fireman for the D.L. & W. Railroad, in Hoboken, New Jersey and he was residing in his parents home at 178 Duffield Street. The record listed his height and build as medium, and he had brown eyes and black hair. John (Jr.’s) mother, Maggie, was listed as his next of kin. His father John (Sr.) had passed away earlier the same year.

Less than one month after registering for the draft, John (Jr.) passed away on October 2, 1918. His cause of death was listed as “labor pneumonia”; although it likely meant to read lobar pneumonia, which affects one lung. He never married and did not have children.

Download Research Report for John A. Munroe (aka Monroe) Jr. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Elizabeth Johnson (1861-1890) was the first burial in Grave 67. There is minimal information about her and it’s difficult to determine her relationship to the Munroe and Johnson families. According to information from her death certificate, Elizabeth was 29 years old when she died on May 25, 1890, from pneumonia, phthisis, and asthenia – likely caused by tuberculosis. She was recorded as married at the time of her death, although her husband’s name is unknown. She had been residing at 373 Hudson Avenue, in Brooklyn, New York, which is in downtown Brooklyn. She was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, as were both her parents.

Download Research Report for Elizabeth Johnson. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Maggie L.B. Johnson (aka Maggie L. Brown Johnson) (1878-1903) was the second burial in Grave 67. Like Elizabeth, there is little information about her and her connection to both families. However, at the time of her death, in 1903, she was residing at the same address as John (Jr.)(1888-1918), who was later interred with her – 94 Willoughby St. On September 19, 1903, at age 25, Maggie passed away from a pulmonary hemorrhage caused by tuberculosis. She was married at the time of her death, although her husband’s name is unknown. Her father was listed on her death certificate as Joseph Brown.

Download Research Report for Maggie L.B. Johnson. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Grave 69: Peter Johnson and William Russell Johnson

Peter Johnson, born December 1, 1823, died on May 14, 1901, interred May 17, 1901.

William Russell Johnson, born 1858, died on November 9, 1914, interred November 13, 1914

Peter Johnson (1823-1901) is the uncle of William Russell Johnson (1858-1914), who is interred with him. Peter Johnson had several siblings, including two brothers, Daniel and James (Jr.), who was the father of William Russell Johnson.

Peter was born on December 1, 1823 in New York City. His parents were James Johnson and Lucy (Peters) Johnson, both born in New York. He was baptized at Greenwich Dutch Reformed Church in Manhattan on December 3, 1823. His parents were married in the same church 10 years prior, on September 4, 1813, and became church members on January 9, 1814.

We could not find records for Peter’s early life, but by the 1880 census, 56-year-old Peter was married to Sarah J. Johnson (48), and has at least two adult children, Eliza Augusta (21) and Jane Elizabeth. He resided at 25 Clarke St. in Manhattan, a street which was absorbed into Sixth avenue between Broome and Spring during the 1920s. His daughter Eliza continued to reside at that address at the time of his death.

Peter worked as a a gold and silver refiner for most of his adult life, later transitioning into the real estate industry and working as a jeweler. In the 1891 City Directory, 68-year-old Peter was working in real estate. The next year’s directory described him as a jeweler, still residing at 25 Clarke St. However, by 1900, 76-year-old Peter had moved to Long Island. The 1900 census recorded Peter as a boarder at a farm in Islip, New York, in Suffolk County, owned by 50-year-old Louisa Duffin, who was Black. Both Peter and Louisa were widowed. Peter’s occupation was recorded as “landlord,” which likely refers to his involvement in real estate.

The next year, on May 14, 1901, Peter passed away in North Islip, New York. His cause of death was recorded by Green-Wood as a hemorrhage. He left behind a will, bequeathing his brother Daniel Johnson, residing at Long Branch, New Jersey, the sum of $500, which would be worth $50,000 or more today. The remainder of his estate was bequeathed to his daughter Jane Elizabeth Pickett, residing at New Haven, Connecticut, his daughter, Eliza Augusta White residing at 25 Clarke Street, New York City, and his nephew William Russell Johnson, residing in the Borough of Brooklyn, City of New York, to share and share alike. William Russell Johnson and Peter’s son-in-law Emmett W. White are appointed executors of Peter’s estate.

Download Research Report for Peter Johnson. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Thirteen years later, William Russell Johnson (1858 – 1914) was interred with his uncle Peter Johnson (1823-1901). At the time of his death, William was a prominent figure known for both his political activism in the Democratic party and his philanthropic work within the Black community. There are many newspaper articles featuring him. He died with a substantial estate, noted in his probate documents as $1000 in cash and $15,000 in real estate, which would be worth over $500,000 today. It’s unclear why both of their graves remained unmarked.

As reported in The New York Age, 57-year-old William passed away while visiting the home of Charles H. Lansing, at 570 Quincy St. in Brooklyn, after having ill health the previous week. William worked for the Department of City Works of Brooklyn for more than two decades, where he was a clerk in charge of payrolls. His cause of death was malignant endocarditis, which is an inflammation of the heart.

William Russell Johnson was born in New York City in July 1857. The 1860 census shows that 3-year old William was living with his parents James Johnson (Jr.) (35) and Elizabeth (34), as well as his brother, James H. (10), and sister, Juliana (8). His father, James Johnson (Jr.), was born in New York, while his wife Elizabeth was born in Virginia. At the time of the census, William’s father was working as a waiter. The family was counted on Schedule 1, which was designated for “free inhabitants.” Schedule 2 was used for “slave inhabitants.”

In 1870, 12-year-old William Russell Johnson was still residing in New York City with his parents, James (53) and Elizabeth (50, note that these ages are inconsistent with the previous census), and older siblings, James H. (19) and Julia (17). At the time of the census, William and his sister were attending school, and his father was working as a truck driver. His mother’s employment was listed as “goes out washing.” They appear to share their home with the Willett family: Louis (48), Mary Ann (49), Mary (21), George (19), William (14), Annie (10), Edward (9), and John (6).

There is little information about William Russell Johnson between 1870 and 1890, when newspaper records show he was becoming a more active public figure. In 1894, he won un upset victory to become president of The Society Sons of New York, headquartered at 153 W. 53rd St. in Manhattan. The all-Black social club, founded in 1884, aimed to create fraternity between Black professional men, including lawyers, merchants and writers. Later, the club added charity to its mission, offering “relief” to people of color in need. When Johnson was elected, the club had 300 members and offered a variety of services including a library, card room, billiard room, cafe, meeting parlors and event hall.

Four years later, in 1898, William Russell Johnson was named the leader of the Colored Democrats of the Borough of Brooklyn, a group which was affiliated with Tammany Hall. An October 31, 1899 article in The Brooklyn Citizen describes Johnson’s “caustic arraignment of the Republican party for its denial of manhood rights to the Afro Americans.” Johnson consistently advocated for Black voters to align, and unify, within the Democratic party, which he believed the party would reward by investing in causes that uplift Black voters. Many articles describe Johnson as popular, although he was not without critics. He is referred to in The Brooklyn Citizen, a white-run newspaper, as the “Beau Brummell of negro democracy” (Brummell was an English politician that became associated with fashion and good looks) and the “Chesterfieldian gentleman of the Water Department” (Chesterfield was an English statesman known for his elegant manners and writings on principles of conduct). To this reader, these comments appear to be barbs, reducing him to a dandy. An October 19, 1900 article reports that Johnson’s efforts to unify factions within the Black democratic party are complicated by an accusation that Johnson took more than his share of campaign funds and distributed it to members of his own delegation. The competing faction claimed to have seen “the W.R. Johnson boys flashing gold certificates around the places that they frequent” when they themselves were “dead broke.” The accusation resulted in a protest at the headquarters of Chairman John Shea, where the rival faction called for Johnson to return the check. The protest was reported to dissipate only when Chairman Shea promised that “each one should have as much ‘dough’ as they wanted.”

By 1905, 47-year-old William Russell Johnson was a lodger at 94 Johnson Street, in Brooklyn. He stayed at this residence, the home of Peter and Elizabeth Downing, and their daughter, Lena, from 1896 onward.

From 1906 until his death in 1914, Johnson became involved in fundraising for the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. The Black-founded organization was located in the Weeksville neighborhood of Brooklyn from 1866 until 1918. By 1906, the organization was in dire financial straits. This initiated a multi-year fundraising push, involving several prominent Black philanthropists. The efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and the organization shuttered in 1918. In 1906, Johnson served as a Master of Ceremonies for the Orphanage’s second benefit, and in 1910 he was listed as the treasurer of the fundraising committee. In April 1914, a few months before his death, he attended a memorial benefit for the orphanage.

On William Russell Johnson’s death certificate, his cousin, Arthur Johnson, was recorded as the executor of his will. He was also listed as widowed, although there is no record of his marriage or his wife’s name. On December 8, 1914, William Russell Johnson’s brother James H. Johnson, who resided in Chicago, petitioned the court to be recognized as the sole heir. The petition claimed that after a diligent search, no will and testament was found, which would trigger intestate succession laws. Without a surviving spouse, parents, or children, the law would favor the surviving siblings.

Download Research Report for William Russell Johnson. Compiled by Michele Dubal.

Lot 5499

Grave 8: Joseph E. Hyde, Elizabeth Hyde, Joseph B. Jones and Jessie E. Jones

Mary Bartlett (removed) died September 6, 1880, interred September 7, 1880, disinterred May 11, 1896 and removed from Green-Wood.

Joseph E. Hyde, born 1823, died May 17, 1896, interred May 19, 1896

Elizabeth Hyde, born 1823, interred November 21, 1902

Joseph B. Jones, born 1869, died January 4, 1926, interred January 6, 1926

Jessie E. Jones, born 1847, died February 18, 1931, interred February 20, 1931

In the 1800s, disinterment was not unusual. Mary Bartlett (1846-1880, removed) was the first burial in Grave 8. She died on September 6, 1880 and was buried at Green-Wood the next day. She was 34 years old, married, and died of phthisis. This generally referred to pulmonary tuberculosis, which was a chronic and degenerative illness. Green-Wood’s burial records are the only record we could find for her, which lists her birthplace as Ohio. Sixteen years after her burial, on May 11, 1896, she was disinterred and removed from Green-Wood by R.F. Routh. I imagine that her family, if still based in Ohio, had saved enough money to bring her home. I wonder if she had travelled to New York from Ohio looking for treatment for her illness.

The now vacant plot was sold to another family. Eight days later, Joseph E. Hyde (1823-1896) was interred in Grave 8. He was 72 years old and his cause of death was bronchitis. He was buried with his wife Elizabeth Hyde (1823-1902), his daughter Jessie E. Jones (1847-1931), and Jessie’s adult son Joseph B. Jones (1869-1926). His daughter, Jessie, paid $31 to purchase the plot.

The Hyde and Jones family immigrated from England between 1867 and 1869. Joseph and Elizabeth’s son Joseph Hyde (Jr.), who is not buried at Green-Wood, immigrated first, aboard the ship Louisiana, leaving from Liverpool, England and arriving in New York on April 21, 1867. Although the ship register lists his age as 20, later census records put his age at 17. He was listed as a laborer.

The next year, Joseph (Jr.)’s sister Jessie immigrated, arriving on April 24, 1868 from Liverpool on the ship Alippo. She was 21 and travelled alone with her son Henry, who is listed as 2 years old. Later census records show the age of her second son, Joseph B. Jones, who was born in New York, as just one year younger. I imagine she was pregnant at the time of her immigration. Later records that describe Jessie as a widow suggest that her husband, Thomas L. Jones, passed away in England before her immigration.

Their parents, Joseph E. Hyde (Sr.) and Elizabeth Hyde, immigrated together on May 17, 1869 on a ship called “City of Brooklyn.” They were 45 and 46 years old at the time of their immigration. Their names are misspelled on the register, reading as “Joseph Hide and Eliza.”

On the 1875 census, the extended family was living together in Brooklyn. Jessie was the head of household and worked as a music teacher with two children. Jessie’s brother Joseph (Jr.) was unmarried and living with them, working as a printer. Citizenship for all except Jessie’s two sons was recorded as “alien.” On the 1880 census, the living arrangements remained the same, although Joseph (Sr.) had been unemployed for over 12 months and Joseph (Jr.) began to work as a collector. Their races were recorded as white.

By the 1905 census, both of Jessie’s parents had passed away and were buried together at Green-Wood. Elizabeth outlived her husband by six years and died in 1902, at the age of 79-years-old, of nephritis, a kidney disease. Jessie and her adult son Joseph B. Jones lived together at 432 Tompkins Avenue in Brooklyn. The 1905 census worker mistook them for a married couple, crossing out “wife” with the correct relation “mother.” Jessie continued to work as a music teacher, while her son was unemployed.

Fifteen years later, in 1920, mother and son still lived together on Tompkins Ave, with a 38-year-old boarder named Emma Williams. They rented, and did not own, their home. At age 73, Jessie was still working. Her son was employed as a broker.

Jessie E. Jones outlived her son Joseph B. Jones. On January 4, 1926, Joseph passed away from cancer of the larynx at 56-years-old. His death record lists him as divorced, although we have no previous record of his marriage or his wife. He was a promoter at the time of his death and Jessie was listed as the executor of his will.

At some point after her son Joseph’s death, the elderly Jessie moved to New Jersey, presumably to be closer to the family of her other son, Henry. On February 18, 1931 she passed away, at age 85, from a cerebral hemorrhage. Her obituary noted that services were held in the home of her granddaughter, Mrs. Charles A. Hulsart before her interment at Green-Wood. She never remarried.

Download Research Report for the Hyde and Jones Family. Compiled by Teddy Sansone and Rowan Renee.

Grave 32: Carl Johan Heidenreich and Bernhardt Forsst

Carl Johan Heidenreich, born 1828, died November 2, 1880; interred November 4, 1880

Bernhardt Forsst, born abt 1867, died September 21, 1885; interred September 23, 1885

Carl Johan Heidenreich (1828-1880) was born in Oslo, Norway on June 28, 1828. He was the eldest of four children, and had three younger sisters. His father, Michael Heidenreich (1801-1857) was a sub-customs officer at Stromso, Norway. His mother was Maren Severine (Waerner) Heidenreich (1808-1882). His father’s position as a civil officer suggests that Carl’s family was middle to upper class, and therefore had access to money and opportunity.

Carl had a degree in the arts. In 1860, he married Lovise Olsen while still living in Oslo. Louise was 25 and he was 32 years old. According to one record, he immigrated to America two years later, in1862, and settled as a merchant in New York.

There are discrepancies in his immigration records. A Geanenet record shows his immigration date as 1862; however we were unable to find records of his journey on a ship manifest or from the Ellis Island Foundation records. Additionally, a 1865 Norwegian census record shows him living Lille Strandgade, Oslo, Norway with his wife, Lovise and a boarder named Johan Smidt. It’s unclear if Carl could have been visiting his wife, who may have stayed behind, or if the earlier record is inaccurate and his immigration took place after 1865. He appears to be the only one of his siblings who immigrated to the United States and there is no record of his wife immigrating with him. Lovise and Carl did not have children.

Although it’s unclear when he arrived, at some point Carl became a patient at Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, which is now located where Columbia University stands. Bloomingdale was a private hospital, which means Carl would have been able to pay for his care. Low-income patients were housed in the New York City Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island). However, neither would have had pleasant conditions. In 1872, the New York journalist Julius Chambers wrote about abuses in Bloomingdale, which led to the release of 12 patients who were not mentally ill, as well as changes to lunacy laws. Use of the terms “insane” and “lunatic” was common in the Victorian era, but reflects outdated and stigmatized views on mental illness and is now considered offensive.

Carl’s cause of death is listed as melancholia. In the Victorian era, the psychiatric diagnosis of melancholia referred to an acute set of symptoms that include psychosis (delusions), catatonia, unrelenting anxiety and depression, as well as suicidal intent. It’s unclear whether Carl’s death was from physical symptoms related to melancholia, or from suicide.

Five years later, Bernhardt Forsst (1867-1885) was interred with Carl Johan Heidenreich (1828-1880). It is not clear why they are buried together, since they appear to have no familial relation. The only record available for Bernhardt is his burial record from Green-Wood, which lists his country of origin and his residence as Germany, suggesting he had no local address or family. He was 18 years old and died by drowning at the public baths at the foot of Conover Street in Brooklyn.

The public baths were essentially floating barges that provided protected area for city residents to swim in the river during the June-September season. They served over a million people per year and offered shared bathing facilities as well as a place for recreation and relief from the summer heat.

It’s possible that both burials may have been arranged by the undertaker, John H. Newman, who was the only common link between the two men. It’s possible that, due to the tragic circumstances, that their burials may have been charitable. Typically charitable burials were not in the public lots, but in private lots that Green-Wood donated to charitable organizations or community associations to manage. There is no record of Carl’s payment for the initial burial; although, due to incomplete records, that does not mean he didn’t pay. Green-Wood records show that Bernhardt Forsst’s representative was charged $5.00 for his interment.

Download Research Report for Carl Johan Heidenreich. Compiled by Lucy Redmond.

About the Research

These biographies accompany the exhibition The Perimeter Path, which focuses on The Green-Wood Cemetery’s public lots. Historically, public lots at Green-Wood were the most affordable burial sites. Over one-third of the 570,000 burials at Green-Wood are located in public lots or single graves (the modern equivalent.) However, many of the graves from the Victorian era and early 20th century were never memorialized. These biographies, all from unmarked graves, aim to make visible what is not apparent in the landscape and bring to the forefront the lives of individuals that have slipped out of our visual, and historical record.

In my preparation for this exhibition, I spent a lot of time with Green-Wood’s burial ledgers, which record biographical details at the time of interment, including name, residence, cause of death, and purchase details. In some cases, this was the only record that a person existed. This small amount of information was enough to draw my attention towards certain individuals – the tragic circumstances of their death, or a question about the relationship between two people buried together – and it helped me choose which people to focus on for further genealogical research. With the support of several generous volunteers – Michele Dubal, Lucy Redmond and Teddy Sansone – we were able to collect more information about these individuals through census records, ship manifests, death certificates, marriage records, and newspaper archives. I used this information to create narrative biographies, bringing life back to these fragmentary details.

Although I am not a historian, I wrote these biographies with an eye towards the conventions of that genre, rather than taking broader artistic license to interpret. I try not to make assumptions that are not backed by records, and when I do make inferences I try to be transparent. My hope is that this will open up the possibility for the reader to interpret these stories and build their own connections, and to place these stories into larger historical context. I have made the original research reports available for a similar reason: because I see this as a start, and not an end, and I want to encourage other researchers to continue.

There are many possible avenues to continue this research. Lot 88, now one of the “Freedom Lots,” was a segregated lot for “Colored adults.” There are people interred in this lot who were born enslaved in both the south and the north, as well as people who travelled to New York during the Great Migration, and freedmen born in New York before emancipation. There are community connections between several of the people and families I researched, and there may be further connections between others in this lot. One possible avenue for research would be to see if there are more connections to the Bridge St. AME Church, which is the oldest documented Black congregation in the Brooklyn-Long Island area, and which was once a stop on the Underground Railroad. Another is the life of William Russell Johnson, who was a prominent public figure at the turn of the 20th century, and who is buried in an unmarked grave.

One area where I do break with convention is my decision to organize this research spatially, by grave, rather than by individual names. This allowed me to look at the relationships between those interred together in a single grave, and in Lot 88, across multiple graves. In some cases there are clear family ties. In others, there appears to be no connection between the individuals. Green-Wood was not a potter’s field, meaning all people presumably paid for their plots. Although there were some charitable burials, these were typically in private lots donated to organizations that managed their distribution to people in need. Green-Wood does not have complete records for lot purchases in the public lots for the time periods I researched. I feel like further research in this area could illuminate more about the history of class dynamics at Green-Wood and how it influenced the landscape of the cemetery.

Additionally, I want to thank Stacy Locke, Jeff Richman and Gabrielle Gatto for their assistance navigating archives, connecting me to volunteers and advising me on how to structure this research.